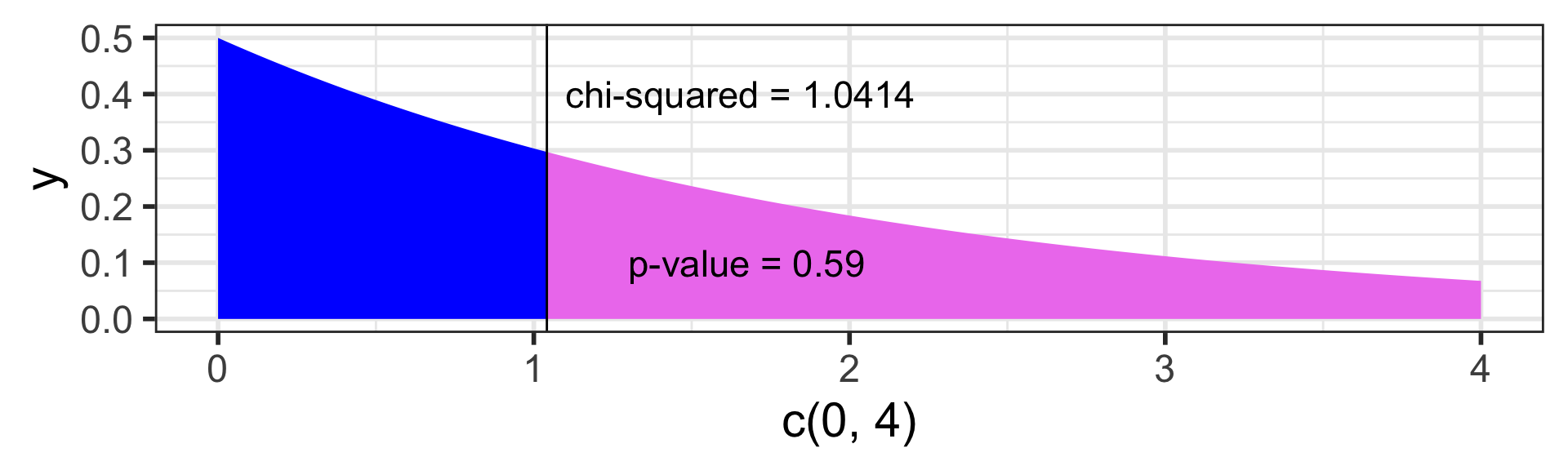

ggplot(NULL, aes(c(0,4))) + # no dataset, create axes for x from 0 to 4

geom_area(stat = "function", fun = dchisq, args = list(df=2),

fill = "blue", xlim = c(0, 1.0414)) +

geom_area(stat = "function", fun = dchisq, args = list(df=2),

fill = "violet", xlim = c(1.0414, 4)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 1.0414) + # vertical line at x = 1.0414

annotate("text", x = 1.1, y = .4, # add text at specified (x,y) coordinate

label = "chi-squared = 1.0414", hjust=0, size=6) +

annotate("text", x = 1.3, y = .1,

label = "p-value = 0.59", hjust=0, size=6) Day 13: Chi-squared tests (Sections 8.3-8.4)

BSTA 511/611

OHSU-PSU School of Public Health

2024-11-18

MoRitz’s tip of the day

Add text to a plot using annotate():

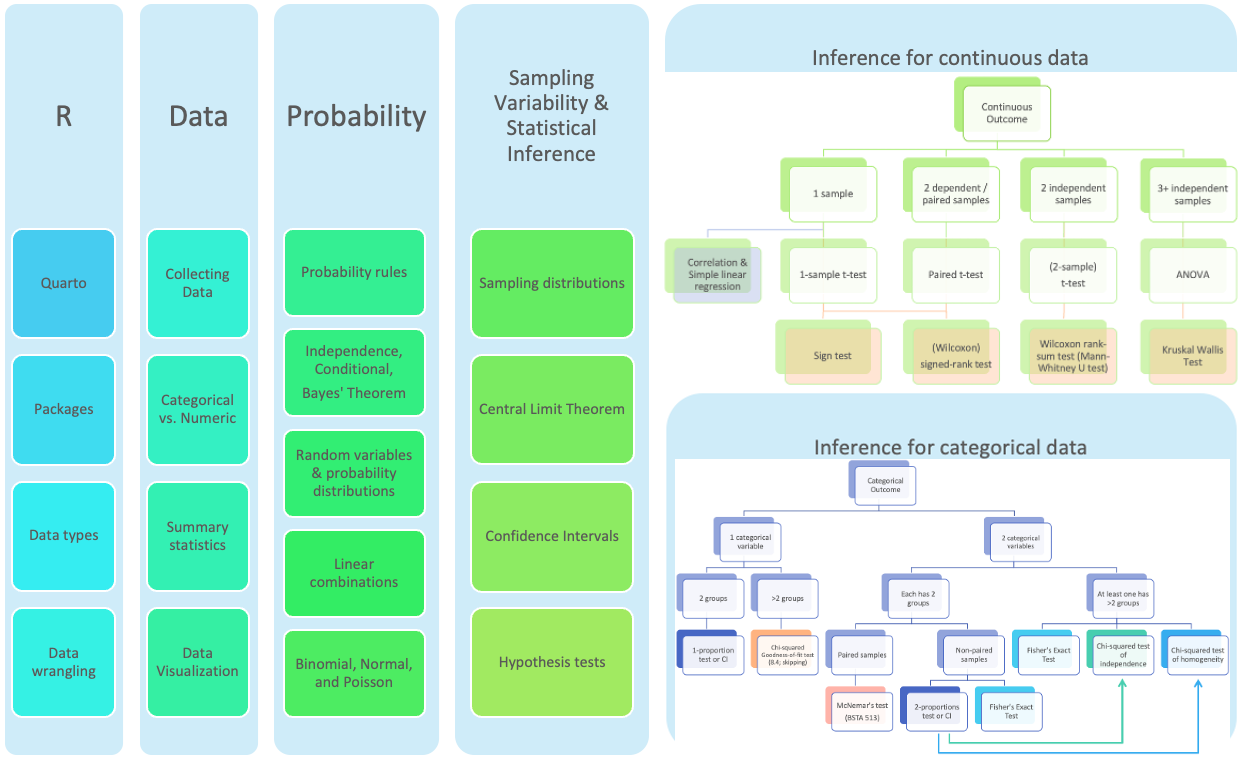

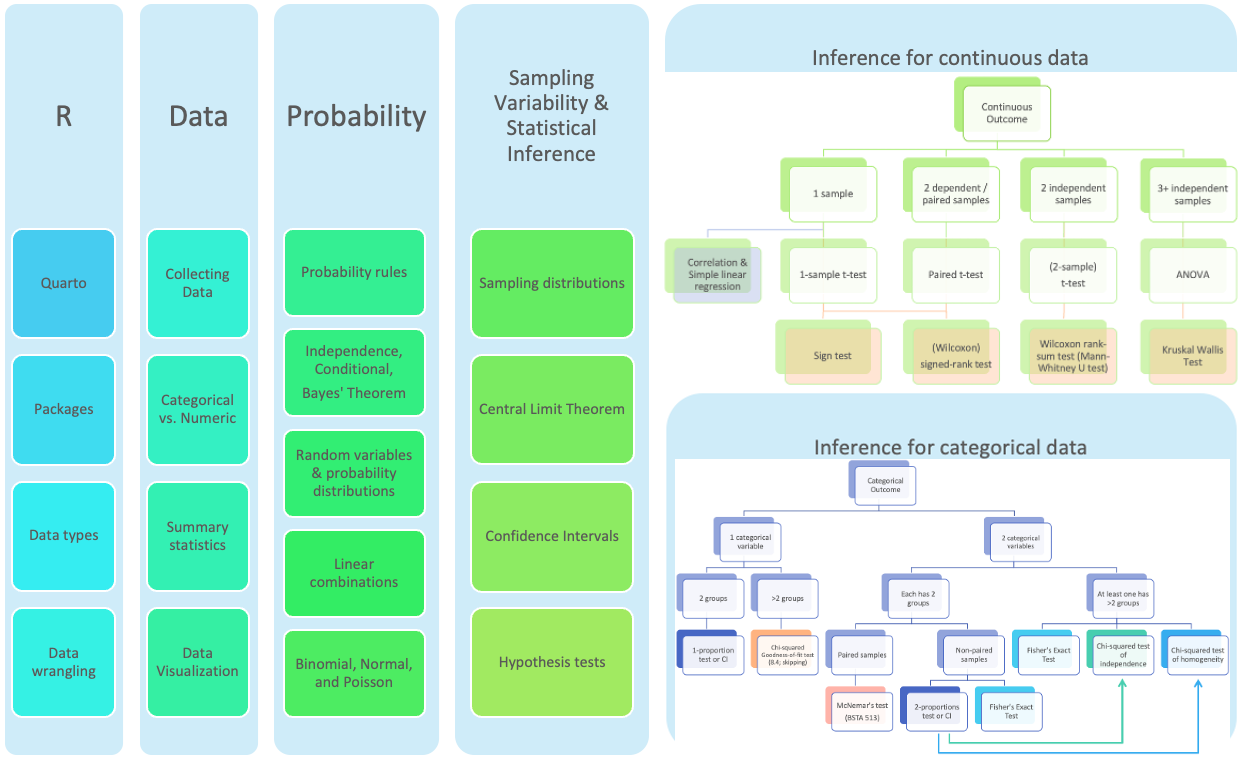

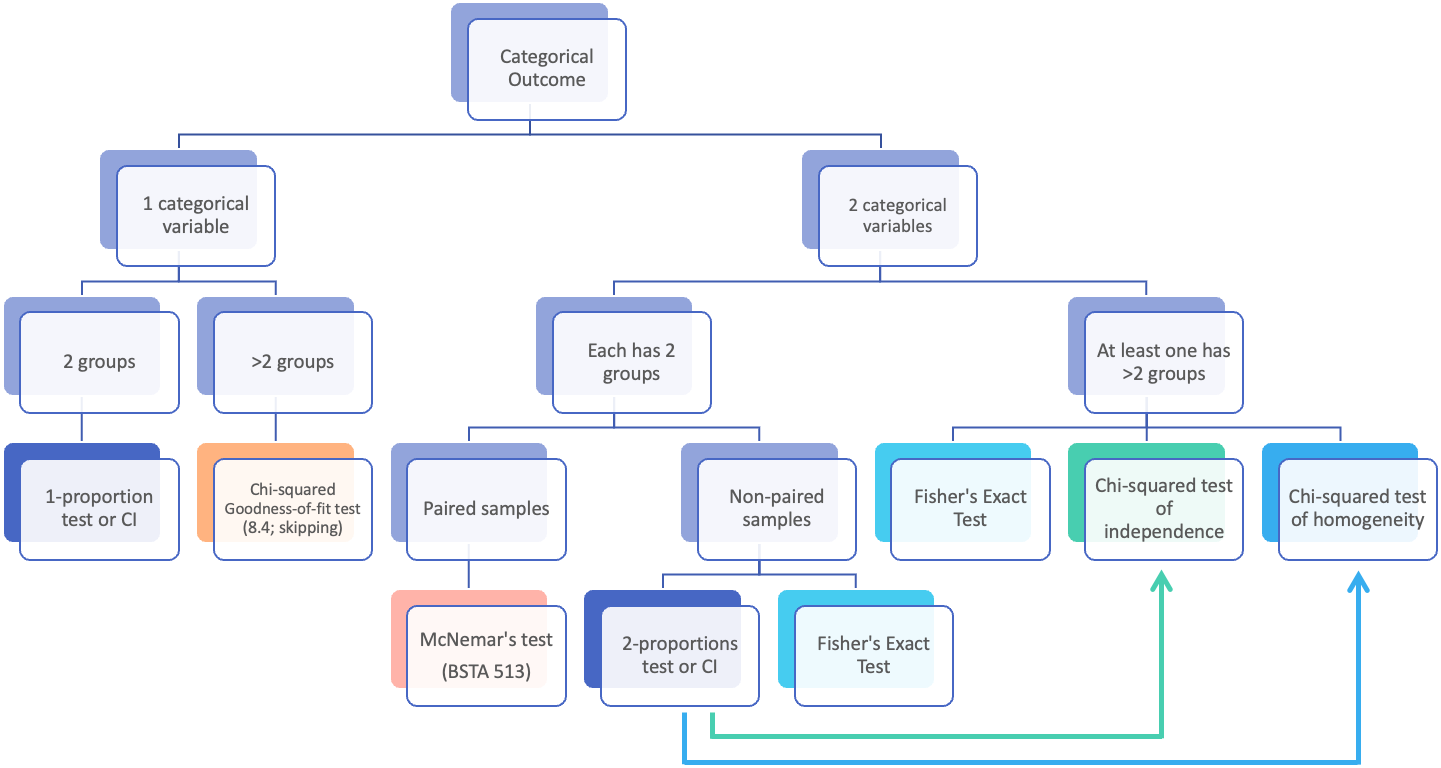

Where are we?

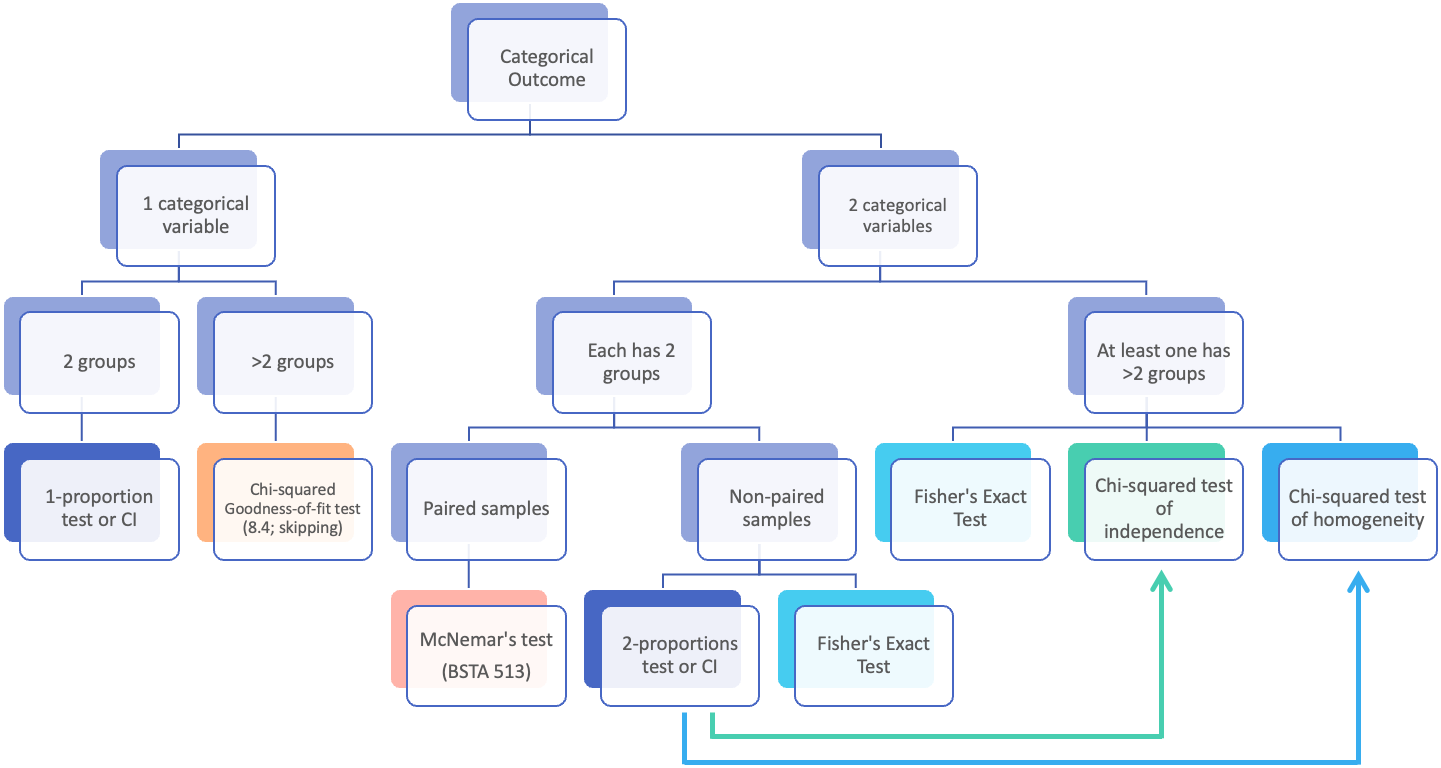

Where are we? Categorical outcome zoomed in

Goals for today (Sections 8.3-8.4)

- Statistical inference for categorical data when either are

- comparing more than two groups,

- or have categorical outcomes that have more than 2 levels,

- or both

- Chi-squared tests of association (independence)

- Hypotheses

- test statistic

- Chi-squared distribution

- p-value

- technical conditions (assumptions)

- conclusion

- R:

chisq.test()

- Fisher’s Exact Test

- Chi-squared test vs. testing difference in proportions

- Test of Homogeneity

Chi-squared tests of association (independence)

Testing the association (independence) between two categorical variables

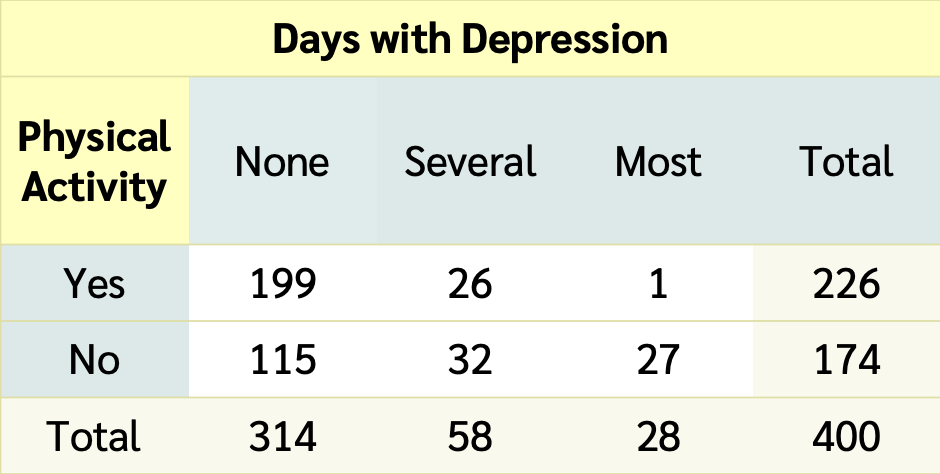

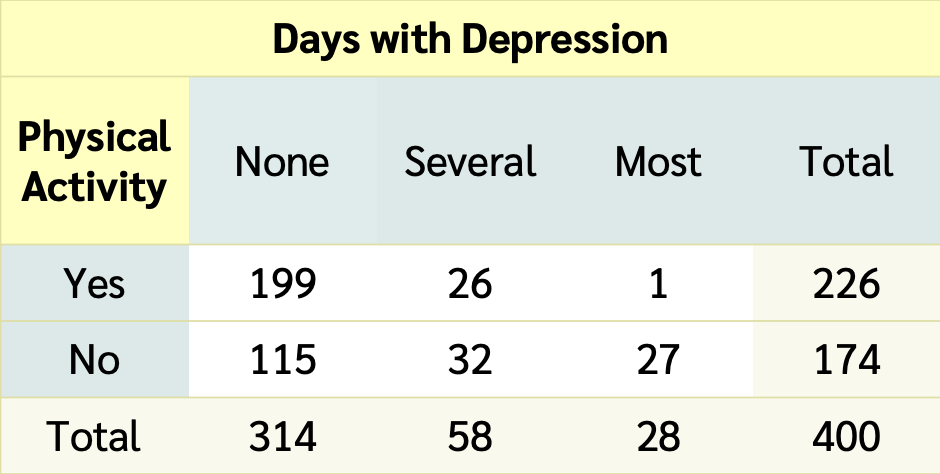

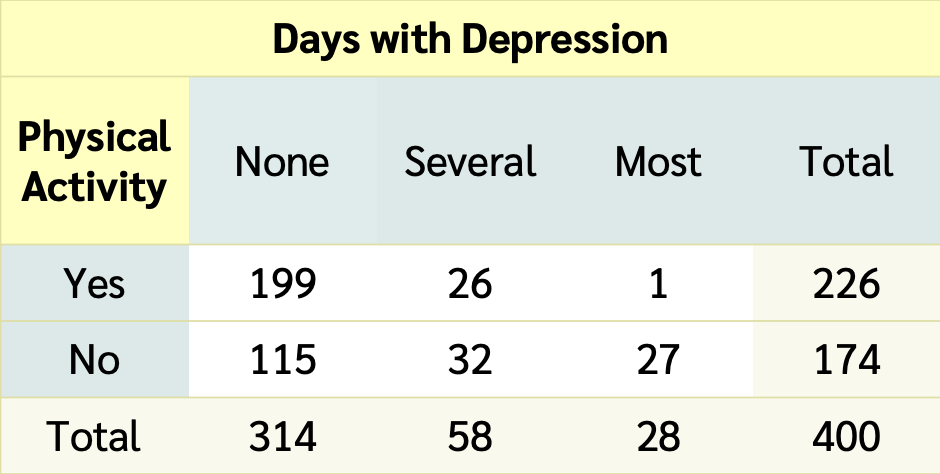

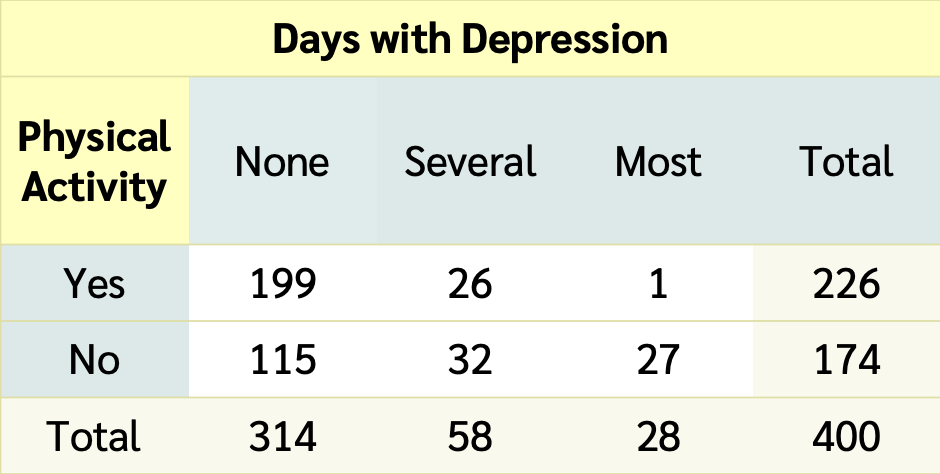

Is there an association between depression and being physically active?

- Data sampled from the NHANES R package:

- American National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys

- Collected 2009-2012 by US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

NHANESdataset: 10,000 rows, resampled fromNHANESrawto undo oversampling effects- Treat it as a simple random sample from the US population (for pedagogical purposes)

Depressed- Self-reported number of days where participant felt down, depressed or hopeless.

- One of None, Several, or Most (more than half the days).

- Reported for participants aged 18 years or older.

PhysActive- Participant does moderate or vigorous-intensity sports, fitness or recreational activities (Yes or No).

- Reported for participants 12 years or older.

Hypotheses for a Chi-squared test of association (independence)

Generic wording:

Test of “association” wording

\(H_0\): There is no association between the two variables

\(H_A\): There is an association between the two variables

Test of “independence” wording

\(H_0\): The variables are independent

\(H_A\): The variables are not independent

For our example:

Test of “association” wording

\(H_0\): There is no association between depression and physical activity

\(H_A\): There is an association between depression and physical activity

Test of “independence” wording

\(H_0\): The variables depression and physical activity are independent

\(H_A\): The variables depression and physical activity are not independent

No symbols

For chi-squared test hypotheses we do not have versions using “symbols” like we do with tests of means or proportions.

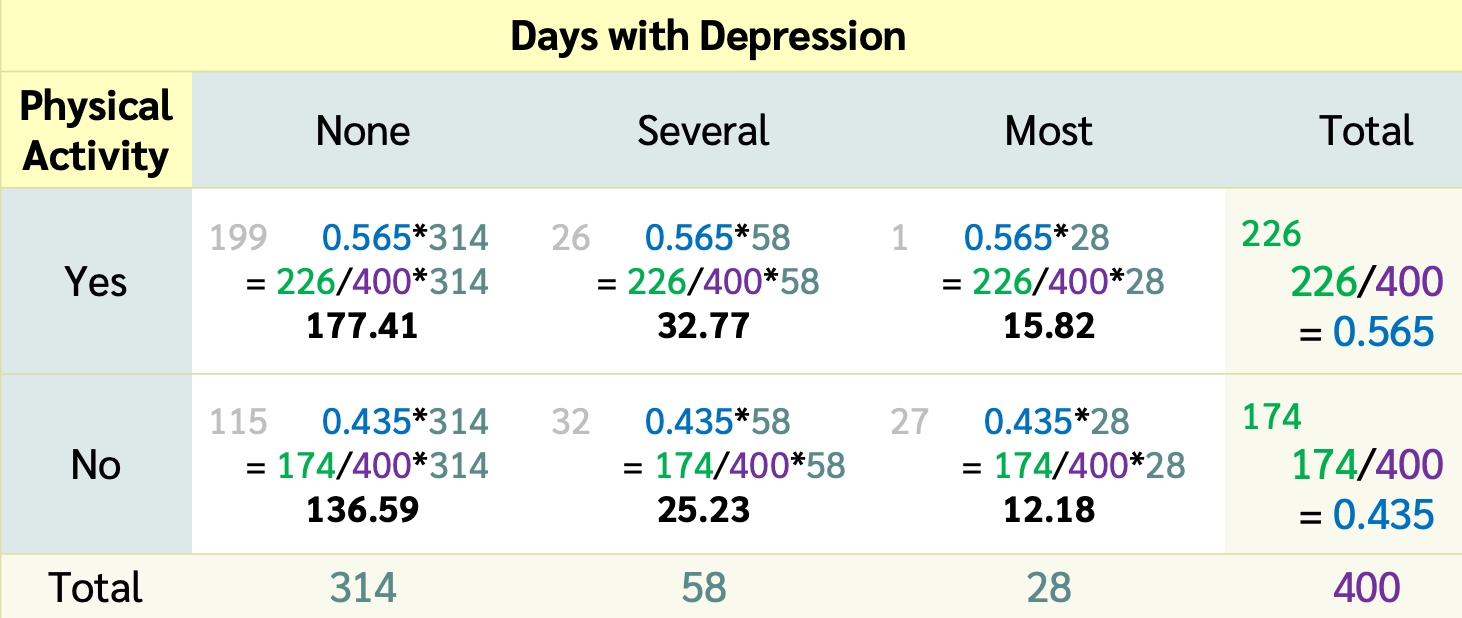

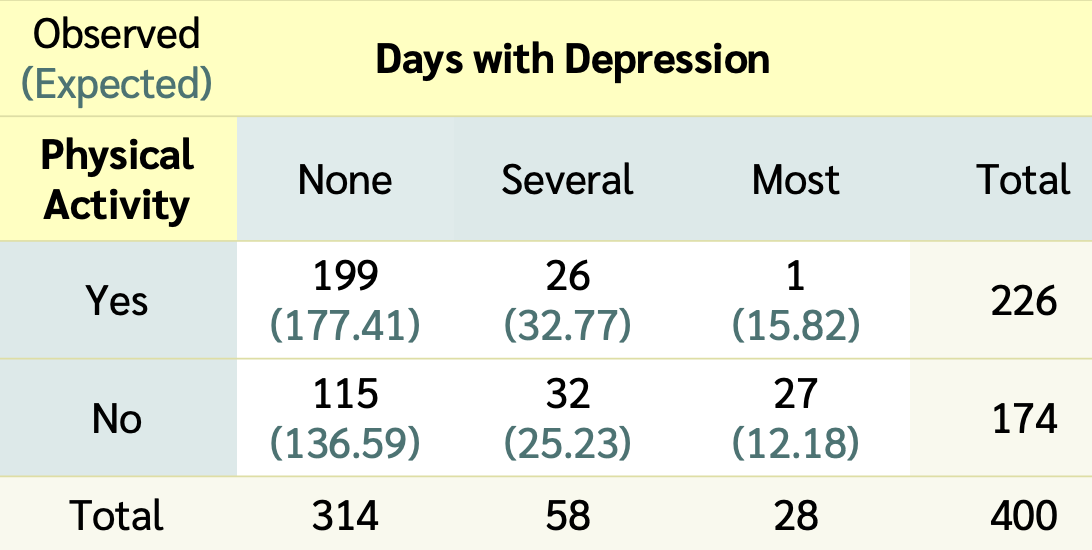

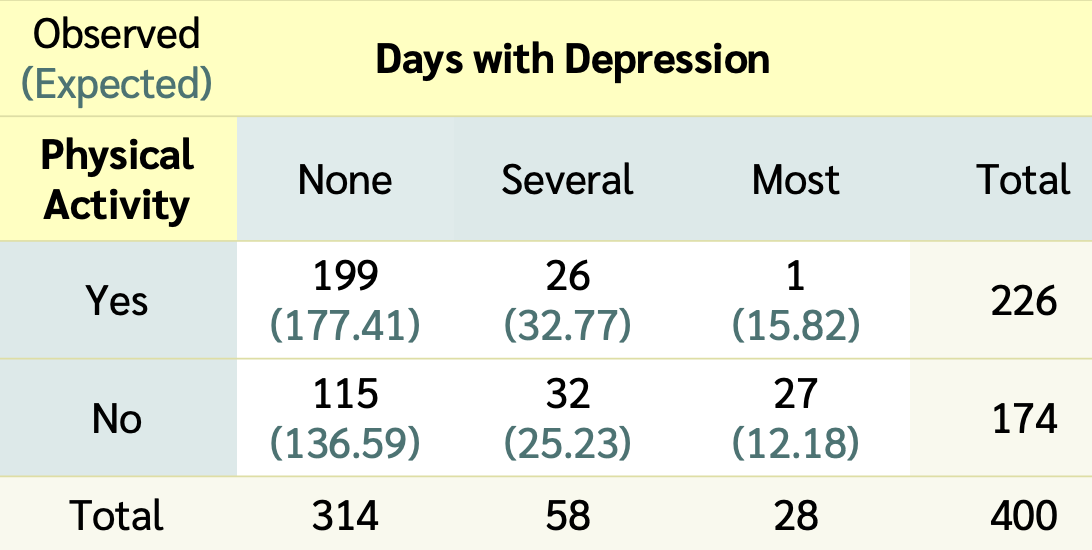

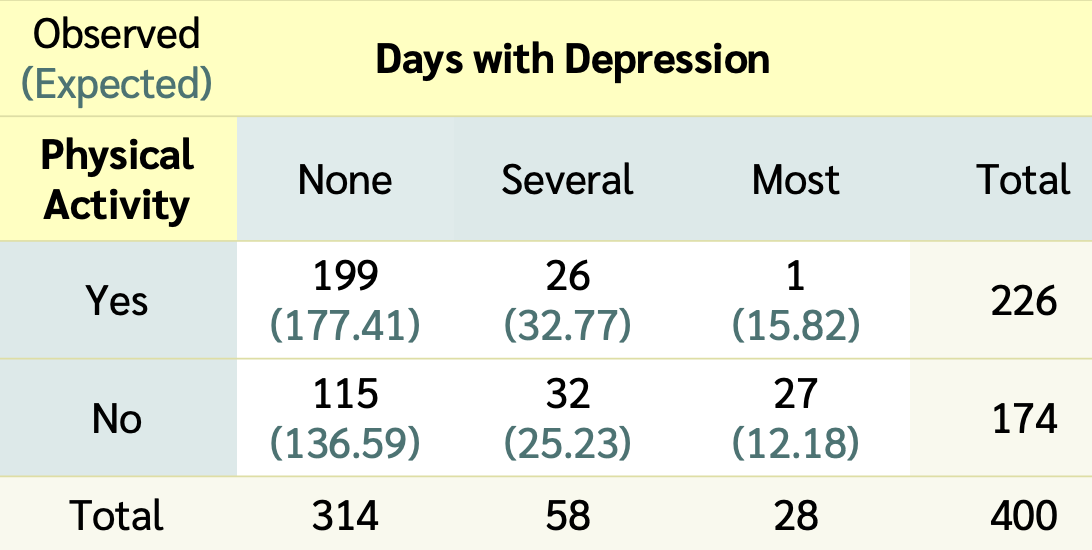

Data from NHANES

- Results below are from

- a random sample of 400 adults (≥ 18 yrs old)

- with data for both the depression

Depressedand physically active (PhysActive) variables.

- What does it mean for the variables to be independent?

\(H_0\): Variables are Independent

- Recall from Chapter 2, that events \(A\) and \(B\) are independent if and only if

\[P(A~and~B)=P(A)P(B)\]

- If depression and being physically active are independent variables, then theoretically this condition needs to hold for every combination of levels, i.e.

\[\begin{align} P(None~and~Yes) &= P(None)P(Yes)\\ P(None~and~No) &= P(None)P(No)\\ P(Several~and~Yes) &= P(Several)P(Yes)\\ P(Several~and~No) &= P(Several)P(No)\\ P(Most~and~Yes) &= P(Most)P(Yes)\\ P(Most~and~No) &= P(Most)P(No) \end{align}\]

\[\begin{align} P(None~and~Yes) &= \frac{314}{400}\cdot\frac{226}{400}\\ & ...\\ P(Most~and~No) &= \frac{28}{400}\cdot\frac{174}{400} \end{align}\]

With these probabilities, for each cell of the table we calculate the expected counts for each cell under the \(H_0\) hypothesis that the variables are independent

Expected counts (if variables are independent)

- The expected counts (if \(H_0\) is true & the variables are independent) for each cell are

- \(np\) = total table size \(\cdot\) probability of cell

Expected count of Yes & None:

\[\begin{align} 400 \cdot & P(None~and~Yes)\\ &= 400 \cdot P(None)P(Yes)\\ &= 400 \cdot\frac{314}{400}\cdot\frac{226}{400}\\ &= \frac{314\cdot 226}{400} \\ &= 177.41\\ &= \frac{\text{column total}\cdot \text{row total}}{\text{table total}} \end{align}\]

- If depression and being physically active are independent variables

- (as assumed by \(H_0\)),

- then the observed counts should be close to the expected counts for each cell of the table

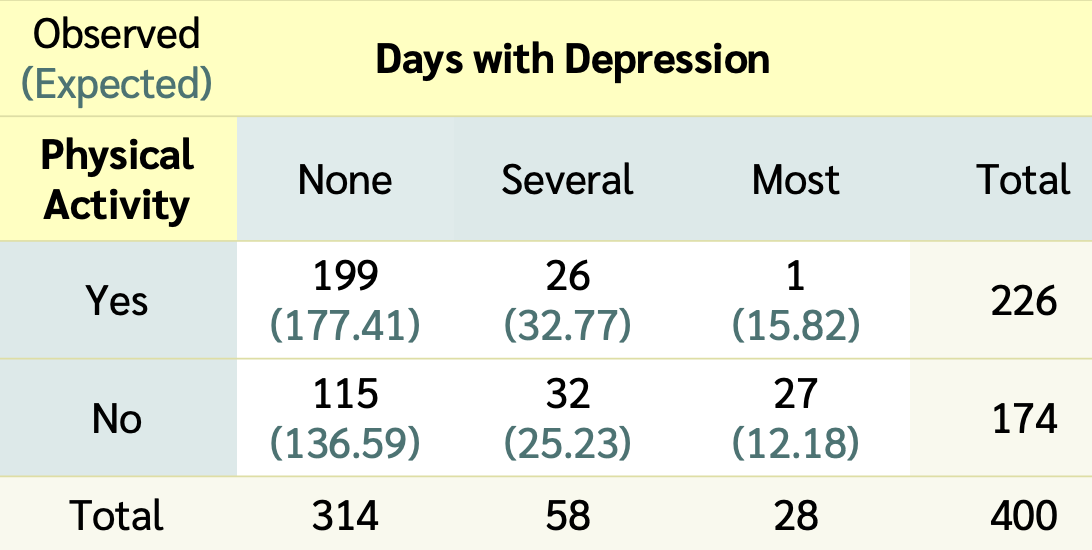

Observed vs. Expected counts

- The observed counts are the counts in the 2-way table summarizing the data

Expected count for cell \(i,j\) :

- The expected counts are the counts the we would expect to see in the 2-way table if there was no association between depression and being physically activity

\[\textrm{Expected Count}_{\textrm{row } i,\textrm{ col }j}=\frac{(\textrm{row}~i~ \textrm{total})\cdot(\textrm{column}~j~ \textrm{total})}{\textrm{table total}}\]

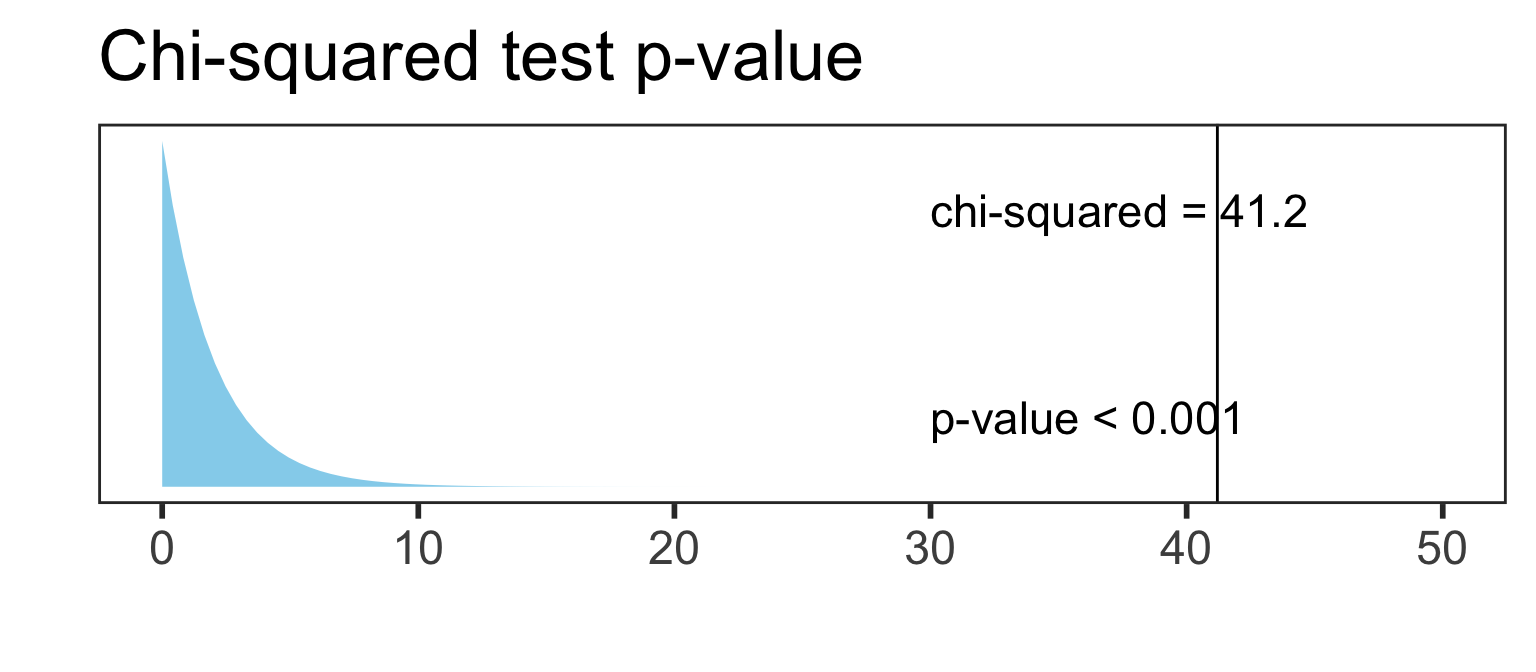

The \(\chi^2\) test statistic

Test statistic for a test of association (independence):

\[\chi^2 = \sum_{\textrm{all cells}} \frac{(\textrm{observed} - \text{expected})^2}{\text{expected}}\]

- When the variables are independent, the observed and expected counts should be close to each other

\[\begin{align} \chi^2 &= \sum\frac{(O-E)^2}{E} \\ &= \frac{(199-177.41)^2}{177.41} + \frac{(26-32.77)^2}{32.77} + \ldots + \frac{(27-12.18)^2}{12.18} \\ &= 41.2 \end{align}\]

Is this value big? Big enough to reject \(H_0\)?

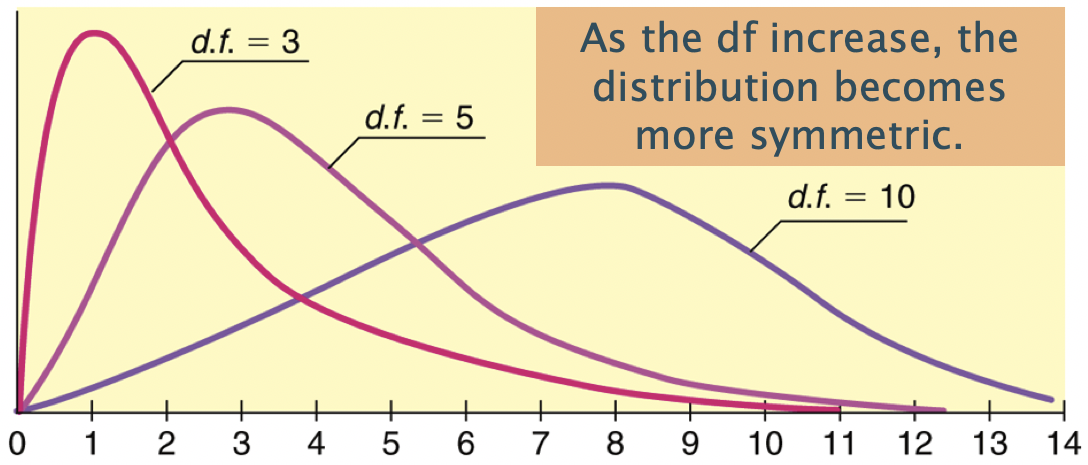

The \(\chi^2\) distribution & calculating the p-value

The \(\chi^2\) distribution shape depends on its degrees of freedom

- It’s skewed right for smaller df,

- gets more symmetric for larger df

- df = (# rows-1) x (# columns-1)

- The p-value is always the area to the right of the test statistic for a \(\chi^2\) test.

- We can use the

pchisqfunction in R to calculate the probability of being at least as big as the \(\chi^2\) test statistic:

What’s the conclusion to the \(\chi^2\) test?

Conclusion

Recall the hypotheses to our \(\chi^2\) test:

\(H_0\): There is no association between depression and being physically activity

\(H_A\): There is an association between depression and being physically activity

Conclusion:

Based a random sample of 400 US adults from 2009-2012, there is sufficient evidence that there is an association between depression and being physically activity (p-value < 0.001).

Warning

If we fail to reject, we DO NOT have evidence of no association.

Technical conditions

- Independence

- Each case (person) that contributes a count to the table must be independent of all the other cases in the table

- In particular, observational units cannot be represented in more than one cell.

- For example, someone cannot choose both “Several” and “Most” for depression status. They have to choose exactly one option for each variable.

- Each case (person) that contributes a count to the table must be independent of all the other cases in the table

- Sample size

- In order for the distribution of the test statistic to be appropriately modeled by a chi-squared distribution we need

- 2 \(\times\) 2 table:

- expected counts are at least 10 for each cell

- larger tables:

- no more than 1/5 of the expected counts are less than 5, and

- all expected counts are greater than 1

Chi-squared tests in R

Depression vs. physical activity dataset

Create dataset based on results table:

Summary table of data:

\(\chi^2\) test in R using dataset

If only have 2 columns in the dataset:

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: table(DepPA)

X-squared = 41.171, df = 2, p-value = 1.148e-09If have >2 columns in the dataset, we need to specify which columns to table:

The tidyverse way (fewer parentheses)

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: .

X-squared = 41.171, df = 2, p-value = 1.148e-09tidy() the output (from broom package):

| statistic | p.value | parameter | method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41.17067 | 1.147897e-09 | 2 | Pearson's Chi-squared test |

Pull p-value

Observed & expected counts in R

You can see what the observed and expected counts are from the saved chi-squared test results:

Why is it important to look at the expected counts?

What are we looking for in the expected counts?

\(\chi^2\) test in R with 2-way table

Create a base R table of the results:

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 199 26 1

[2,] 115 32 27dimnames(DepPA_table) <- list("PA" = c("Yes", "No"), # row names

"Depression" = c("None", "Several", "Most")) # column names

DepPA_table Depression

PA None Several Most

Yes 199 26 1

No 115 32 27Run \(\chi^2\) test with 2-way table:

(Yates’) Continuity correction

- For a 2x2 contingency table,

- the \(\chi^2\) test has the option of including a continuity correction

- just like with the proportions test

- The default includes a continuity correction

- There is no CC for bigger tables

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 199 27

[2,] 115 59dimnames(DepPA_table2x2) <- list("PA" = c("Yes", "No"), # row names

"Depression" = c("None", "Several/Most")) # column names

DepPA_table2x2 Depression

PA None Several/Most

Yes 199 27

No 115 59Output without a CC

Fischer’s Exact Test

Use this if expected cell counts are too small

Example with smaller sample size

- Suppose that instead of taking a random sample of 400 adults (from the NHANES data), a study takes a random sample of 100 such that

- 50 people that are physically active and

- 50 people that are not physically active

Chi-squared test warning

Warning in stats::chisq.test(x, y, ...): Chi-squared approximation may be

incorrect

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: DepPA100_table

X-squared = 2.2195, df = 2, p-value = 0.3296Warning in stats::chisq.test(x, y, ...): Chi-squared approximation may be

incorrect Depression

PA None Several Most

Yes 41.5 4.5 4

No 41.5 4.5 4- Recall the sample size condition

- In order for the test statistic to be modeled by a chi-squared distribution we need

- 2 \(\times\) 2 table: expected counts are at least 10 for each cell

- larger tables:

- no more than 1/5 of the expected counts are less than 5, and

- all expected counts are greater than 1

Fisher’s Exact Test

- Called an exact test since it

- calculates an exact probability for the p-value

- instead of using an asymptotic approximation, such as the normal, t, or chi-squared distributions

- For 2x2 tables the p-value is calculated using the hypergeometric probability distribution (see book for details)

- calculates an exact probability for the p-value

Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data

data: DepPA100_table

p-value = 0.3844

alternative hypothesis: two.sidedComments

- Note that there is no test statistic

- There is also no CI

- This is always a two-sided test

- There is no continuity correction since the hypergeometric distribution is discrete

Simulate p-values: another option for small expected counts

From the chisq.test help file:

- Simulation is done by random sampling from the set of all contingency tables with the same margin totals

- works only if the margin totals are strictly positive.

- For each simulation, a \(\chi^2\) test statistic is calculated

- P-value is the proportion of simulations that have a test statistic at least as big as the observed one.

- No continuity correction

\(\chi^2\) test vs. testing proportions

\(\chi^2\) test vs. testing differences in proportions

If there are only 2 levels in both of the categorical variables being tested, then the p-value from the \(\chi^2\) test is equal to the p-value from the differences in proportions test.

Example: Previously we tested whether the proportion who had participated in sports betting was the same for college and noncollege young adults:

\[\begin{align} H_0:& ~p_{coll} - p_{noncoll} = 0\\ H_A:& ~p_{coll} - p_{noncoll} \neq 0 \end{align}\]

| statistic | p.value | parameter | method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01987511 | 0.8878864 | 1 | Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction |

| estimate1 | estimate2 | statistic | p.value | parameter | conf.low | conf.high | method | alternative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6505576 | 0.6401869 | 0.01987511 | 0.8878864 | 1 | -0.07973918 | 0.1004806 | 2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction | two.sided |

[1] 0.8878167Test of Homogeneity

Running the sports betting example as a chi-squared test is actually an example of a test of homogeneity

In a test of homogeneity, proportions can be compared between many groups

\[\begin{align} H_0:&~ p_1 = p_2 = p_2 = \ldots = p_n\\ H_A:&~ p_i \neq p_j \textrm{for at least one pair of } i, j \end{align}\]

It’s an extension of a two proportions test.

The test statistic & p-value are calculated the same was as a chi-squared test of association (independence)

When we fix the margins (whether row or columns) of one of the “variables” (such as in a cohort or case-control study)

- the chi-squared test is called a Test of Homogeneity

Overview of tests with categorical outcome

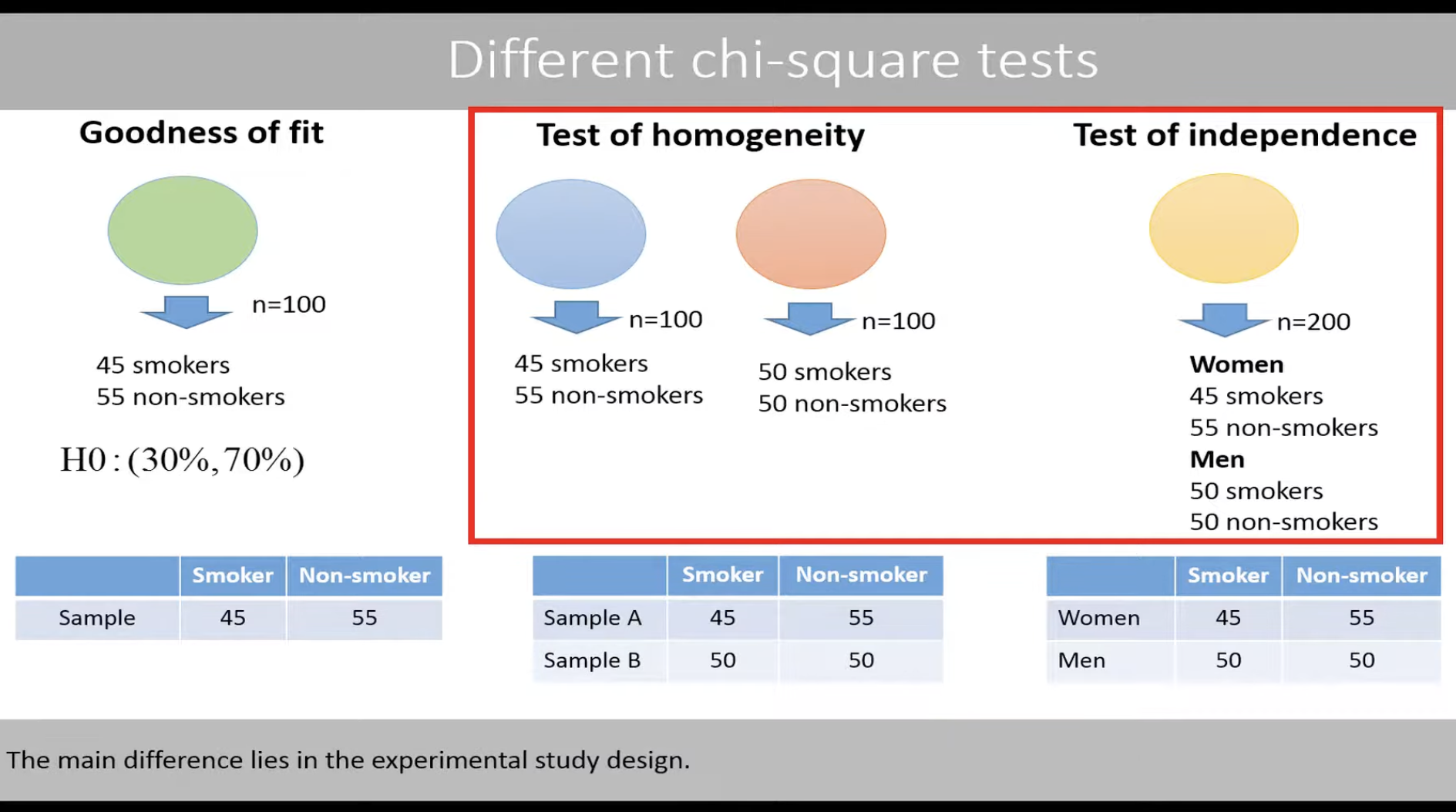

Chi-squared Tests of Independence vs. Homogeneity vs. Goodness-of-fit

- See YouTube video from TileStats for a good explanation of how these three tests are different: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TyD-_1JUhxw

- UCLA’s INSPIRE website has a good summary too: http://inspire.stat.ucla.edu/unit_13/

What’s next?